poetry

-

Home at the Edge of the World: Alameda Poet Laureate Inaugural Poem

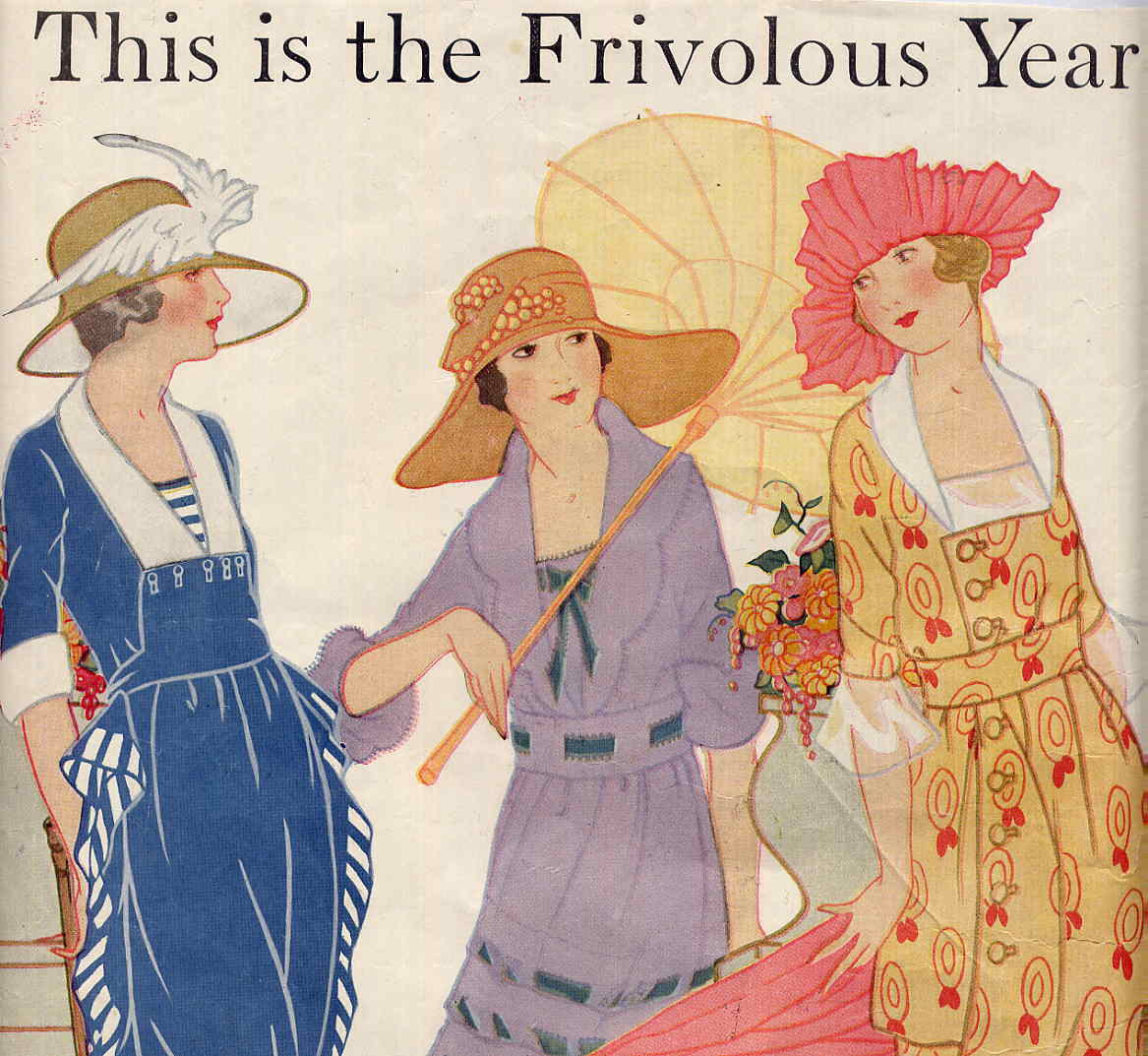

Home at the Edge of the World Alameda Poet Laureate Inaugural Poem There are houses down your shaded streets – beneath your oaks, your ginkos, your avenues of palm – Leaded in glass, shingled in fish-scale, spangled with gingerbread, Victorian ladies tarted up for Carnival, their history and lore curving like a staircase into view. Gentlemen strolled in spats, ladies swung their parasols, bay breezes curling with fog and the clank of halyards, snapping flags. Water, at every turn, glittering to shore, to ship, to ankles and toes. Neptune would have been pleased to see his name emblazoned, to hear the calliope, the splash and crank, the punch of tickets.…

-

Do Not Disturb: Am Writing.

Don’t try and stop me. I have writing to do. I’m writing while I fold laundry and wash dishes. I’m writing while I sit by my husband’s bed awaiting his back surgery. I’m writing while I drive home late at night. I’m writing when I get up at 3 a.m. to let the cat in. Or out. I’m writing when it looks like I’m reading. Or spacing out. Or chopping vegetables. Because, for me, writing doesn’t look like writing until the last 10 percent. “Genius is 10 percent inspiration and 90 percent perspiration.” — Thomas Alva Edison Writing — for me — is like that, too, sort of. It’s all in…

-

April is the Coolest Month #NaPoMo

April is National Poetry Month. As the Poet Laureate of Alameda, I’d like to invite you to crack open a poetry book and read one, just once, this month. Read an old favorite, like T.S. Eliot, perhaps, whose Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock is one of the finest examples of 20th Century poetry (“Let us go then, you and I, When the evening is spread out against the sky like a patient etherized upon a table…”) – or maybe watch performance poets you’ll find on YouTube, like Suli Breaks’ “Why I Hate School but Love Education,” or Savanna Brown’s “What Guys Look for in Girls.” (No, seriously, GO WATCH.) Poetry…

-

Poet Laureate!

Yes, I was chosen to be Alameda’s Poet Laureate in a ceremony at City Hall on September 16. On television and before a full chamber, I read a poem about Alameda, called “Home at the Edge of the World,” the title a nod to one of my mentors, Michael Cunningham (The Hours), and the content a personal and historical journey through Alameda. The poem will be published in the October issue of Alameda Magazine. You can also hear me read it here on Voqel. And with the change of seasons, my calendar is full. I spent September attending as many open mics and writing workshops as possible. I read several…

- authors, book biz, Books, indie pub, novel, Poet Laureate, poetry, quotables, Tongues of Angels, Uncategorized, writing

Poetry Corner — An Interview (from Sweatpants and Coffee)

“Poetry is kind of like Brussels sprouts,” a friend of mine said recently. “Some people love it and most people hate it.” I find this both funny and, sadly, true; sadly because I consider myself a poet – but it took a long time, a lot of work and even more encouragement by fellow poets and mentors to claim that title. The woman who made that tasty analogy is Julia Park Tracey, and she was recently named Poet Laureate for the city of Alameda, where she lives in California. In addition to being newly minted as Poet Laureate, Julia is also an accomplished editor and journalist, and has published books…